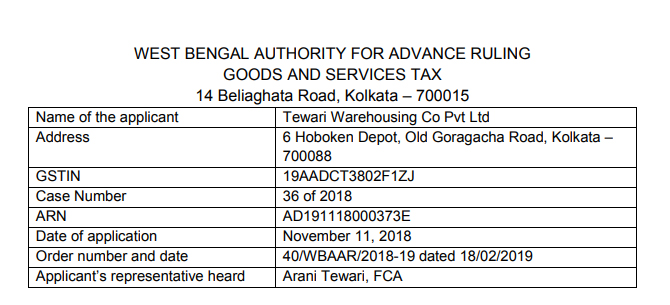

Original copy of GST AAR – Tewari Warehousing

Download the full pdf of GST AAR – Tewari Warehousing by clicking the image below

- The Applicant, stated to be supplying warehousing services, is constructing a warehouse on leasehold land, using pre-fabricated technology. According to the Applicant, it can be dismantled and reconstructed at a different location. He seeks a ruling on whether the input tax credit is admissible on the inward supplies for the construction of the said warehouse.

The above question is admissible under section 97(2)(d) of the CGST/WBGST Act, 2017 (hereinafter collectively called „the GST Act).

The Applicant declares that the issue raised in the application is not pending nor decided in any proceedings under any provisions of the GST Act.

The officer concerned has raised no objection to the admissibility of the Application.

The Application is, therefore, admitted. - In his written submission the Applicant describes the property under construction as „Prefabricated Warehousing System‟ (hereinafter „the System‟). It is being purchased from M/s Pennar Engineering Building Systems Ltd (hereinafter the Vendor). The Applicant has annexed the literature (Annexure 4 to the Application) in which the Vendor provides a brief description of the pre-fabricated structures being supplied with pictorial and graphic presentations. The Applicant further submits that the System is movable property and, therefore, the provisions of section 17(5) (c) & (d) of the GST Act, blocking input tax credit on inward supplies for the construction of immovable property, is not applicable.

The Applicant argues that anything embedded in the ground and is not movable (except in certain cases like standing timber, grass, growing crops and the like) or anything that is permanently fixed to such things which are so embedded to the ground can be called an immovable property.

On the other hand, the System, according to the Applicant‟s submission, is fixed by anchor bolts to a low RCC platform embedded to the ground, and it is the only civil structure. The rest of the structure, like columns, beams, rafters, wall sheets, roof shed, etc. are all joined with one another by nuts and bolts, and can be easily dismantled and restructured at another location.

The low-rising RCC platform is, of course, permanently embedded to the ground. However, according to the Applicant, the warehousing system built thereon, can be dismantled, and thus reduces repeated capital expenses in the event of a shift of location. Moreover, the question of the treatment of a property that is attached to a structure permanently embedded on earth has a long legal history. The consensus that has emerged favours treatment of such property as movable or immovable depending on the extent of annexation to the permanently embedded structure and the object of such annexation.

According to the Applicant, if the nature of annexation is such that an item so annexed can be removed without any damage and future enjoyment of that item in a similar capacity is not affected, such an item will not be considered to be immovable property. He refers to the apex court‟s judgments in Solid & Correct Engineering Works [(2010) 252 ELT 481 (SC)] and Sirpur Paper Mills Ltd [97 ELT 3 (SC)].

He further submits with illustrations that the warehouse is nothing more than an assembly of the System, which is pre-fabricated and pre-engineered components, fixed together in a modular form with nuts and bolts and without welding so that it can be easily unfixed. The utility of the RCC platform on which the System is being fixed is limited to allowing the warehouse to be set up and no further. It is the System that is beneficially enjoyed, not the RCC structure. - “Immovable property” is not defined under the GST Act. The term „goods‟ is defined under Section 2(52) of the GST Act as all kinds of moveable properties other than money and securities but includes actionable claim, growing crops, grass and things attached to or forming part of the land which are agreed to be severed before supply or under a contract of supply.

Property other than goods, money, and securities should, therefore, be considered as ‘immovable property’ under the GST Act.

However, in the absence of a definitive explanation under the GST Act, recourse is being taken to other allied Acts dealing with “property” to determine the definition of “Immovable property”.

It is seen that Section 3(26) of the General Clauses Act, 1897 defines “Immovable Property” as to include land, benefits to arise out of the land, and things attached to the earth, or permanently fastened to anything attached to the earth; Section 3 of the Transfer of Property Act, 1882 simply provides that unless there is something repugnant in the subject or context „immovable property‟ does not include standing timber, growing crops or grass. The Section, however, defines the term “attached to the earth” to mean (a) rooted in the earth, as in the case of trees and shrubs, (b) embedded in the earth, as in the case of walls or buildings, and (c) attached to what is so embedded for permanent beneficial enjoyment of that to which it is attached.

The essential character of „immovable property‟, as emerges from the above discussion and relevant to the present context is that it is attached to the earth, or permanently fastened to anything attached to the earth, or forming part of the land and not agreed to be severed before supply or under a contract of supply. - In Triveni Engineering & Industries Ltd [(2000) 120 ELT 273 (SC)] the Apex Court observes that while determining whether an article is permanently fastened to anything attached to the earth both the intention as well as the factum of fastening has to be ascertained from the facts and circumstances of each case.

In S/S Triveni N L Ltd [RN – 910, 911 & 912 of 2001 (All)] Allahabad High Court observes that „permanently fastened to anything attached to the earth‟ has to be read in the context for the reason that nothing can be fastened to the earth permanently so that it can never be removed. If the article cannot be used without fastening or attaching it to the earth and is not removed under ordinary circumstances, it may be considered permanently fastened to anything attached to the earth.

Furthermore, in the context of the GST Act, if the article attached to the earth is not agreed to be severed before supply or under a contract for the supply, it ceases to be goods and, for that matter, a moveable property. - In the case of Solid & Correct Engineering Works (supra) that the Applicant refers to, the Apex Court, while examining whether a machine, fixed with nuts and bolts to a foundation, with no intent to permanently attach it to the earth, is an immovable property or not, has held that such an attachment without necessary intent to making it permanent cannot be an immovable property. The emphasis is on the intention of the party. The Apex Court observes that the machine in question can be moved and has indeed been moved after the road construction and repair project, for which it was installed, is completed. However, if a machine is intended to be fixed permanently to a structure embedded in the earth, the moveable character of the machine, according to the Supreme Court, becomes extinct.

In Sirpur Paper Mills Ltd (supra) the apex court has upheld the decision of the Customs, Excise and Gold Tribunal that a papermaking machine, attached to earth for operational efficiency, cannot be an immovable property merely because it is attached to a foundation embedded in the earth. The test is whether the machine can be dismantled and sold in the market. This judgment is based on the premise that the machine and not the foundation to which it is attached is the property being used and enjoyed. It is not relevant in the context where the civil structure embedded on earth forms an integral part of the property. - In the present context, the Applicant is constructing the warehouse on a piece of land, taken on lease from Kolkata Port Trust for a period of thirty years for the purpose of building a storage facility. The intention, therefore, is beneficial enjoyment for more than two decades of the property being built. Unless the business is wound up, the Applicant, after the expiry of the lease, can approach KOPT for granting a fresh lease. The structure being built is, therefore, not for the purpose of temporary enjoyment, but intended to be used as a permanent structure subject to usual business uncertainties.

The concerned officer from the revenue has also pointed out correctly that the System refers only to the pre-fabricated structures that are used for constructing the warehouse and not to the warehouse itself. The core issue in the context of the Application is not the beneficial enjoyment of the System, but of the property of the warehouse being built. Being a storage facility, a warehouse is associated with the space available, whereas the System refers to the materials and structures used for turning the space into a covered storage facility. As technology advances, the engineering for building a factory, house, and even a bridge uses more and more pre-fabricated structures, which have obvious benefits in terms of time and cost. Such building blocks should not, however, be confused with the property being built, which is directly associated with the beneficial enjoyment of the land.

The warehouse is meant for storage of goods that will lie stacked on the floor. Construction of the floor, its load-bearing capacity and the space it occupies is, therefore, critical to the construction of the warehouse. The System that the Vendor supplies, as transpires from the literature annexed to the Application, does not apparently include any specific description of the floor as a pre-fabricated load-bearing structure. Although the written submission made at the time of Hearing refers to the floor as a pre-fabricated structure, description of the System, as the Vendor provides in the literature, does not include any specification. In a cross-sectional diagram of the typical pre-engineered steel building the Vendor provides a vivid pictorial illustration of the various parts of the structure – the walls, roof, doors and windows etc. that will be built upon the floor, but does not provide any description of the floor as a pre-fabricated structure.

The literature refers to wide bay purlins spanning up to 12 M for better shop floor lay out and less foundation cost. It indicates that the Vendor supplies building materials that, in his opinion, provides a more cost effective method to support the foundation for laying out the floor. It does not in any way claim that the floor itself is a pre-fabricated structure detachable from the foundation and associated civil work. In fact, the diagram showing a typical pre-engineered building does not at all include a cross-section of the floor as a prefabricated structure.

It, therefore, appears that the Vendor is not supplying the floor as a pre-fabricated removable structure. The civil work undertaken is meant not only for fixing the prefabricated structure built upon the floor but also for developing the floor space itself. Beneficial enjoyment of the floor so inalienably attached to the land is integral to the enjoyment of the warehouse. - The order of the Uttarakhand AAR in Vindhya Telelinks Ltd [(2018) 97 taxmann.com 564] needs to be distinguished in this context. The ld AAR in Uttarakhand has been dealing with mobile towers fixed to a pit with a concrete base. Clearly, the intention is beneficial enjoyment of the mobile tower and not of the concrete base. The mobile tower can, of course, be easily dismantled and fixed elsewhere. The ld AAR has, therefore, treated the mobile tower infrastructure, including the pole, as movable property. In the case of the warehouse, however, the pre-fabricated movable structures do not constitute the property of the warehouse. They are building blocks applied to a civil structure attached to the land to construct a complete warehouse. The warehouse cannot be conceived without the beneficial enjoyment of the civil structure, which is an integral part of the property. The decision in Vindhya Telelinks Ltd (supra) is not, therefore, relevant. In this connection, reference may be made to clause 4(v) of the Circular No. 58/1/2002-CX dated 15/01/2002, where it is concluded that „if items assembled or erected at site and attached by foundation to earth cannot be dismantled without substantial damage to its components and thus cannot be reassembled, then the items would not be considered as moveable and will, therefore, not be excisable goods.” Clearly, the warehouse cannot be relocated by unfixing the pre-fabricated structures alone. The dismantling of the floor, which is the most important component of the warehouse, is not possible without substantial damage to the foundation.

- The order of the Uttarakhand AAR in Vindhya Telelinks Ltd [(2018) 97 taxmann.com 564] needs to be distinguished in this context. The ld AAR in Uttarakhand has been dealing with mobile towers fixed to a pit with a concrete base. Clearly, the intention is beneficial enjoyment of the mobile tower and not of the concrete base. The mobile tower can, of course, be easily dismantled and fixed elsewhere. The ld AAR has, therefore, treated the mobile tower infrastructure, including the pole, as movable property. In the case of the warehouse, however, the pre-fabricated movable structures do not constitute the property of the warehouse. They are building blocks applied to a civil structure attached to the land to construct a complete warehouse. The warehouse cannot be conceived without the beneficial enjoyment of the civil structure, which is an integral part of the property. The decision in Vindhya Telelinks Ltd (supra) is not, therefore, relevant. In this connection, reference may be made to clause 4(v) of the Circular No. 58/1/2002-CX dated 15/01/2002, where it is concluded that „if items assembled or erected at site and attached by foundation to earth cannot be dismantled without substantial damage to its components and thus cannot be reassembled, then the items would not be considered as moveable and will, therefore, not be excisable goods.” Clearly, the warehouse cannot be relocated by unfixing the pre-fabricated structures alone. The dismantling of the floor, which is the most important component of the warehouse, is not possible without substantial damage to the foundation.

In view of the foregoing, we rule as under

RULING

The warehouse being constructed is immovable property. The input tax credit is, therefore, not admissible on the inward supplies for construction of the said warehouse, as the credit of such tax is blocked under section 17(5)(d) of the GST Act. This Ruling is valid subject to the provisions under Section 103 until and unless declared void under Section 104(1) of the GST Act.

| (SYDNEY D‟SILVA) | (PARTHASARATHI DEY) |

| Member | Member |

| West Bengal Authority for Advance Ruling | West Bengal Authority for Advance Ruling |

References

ConsultEase Administrator

ConsultEase Administrator

Consultant

Faridabad, India

As a Consultease Administrator, I'm responsible for the smooth administration of our portal. Reach out to me in case you need help.