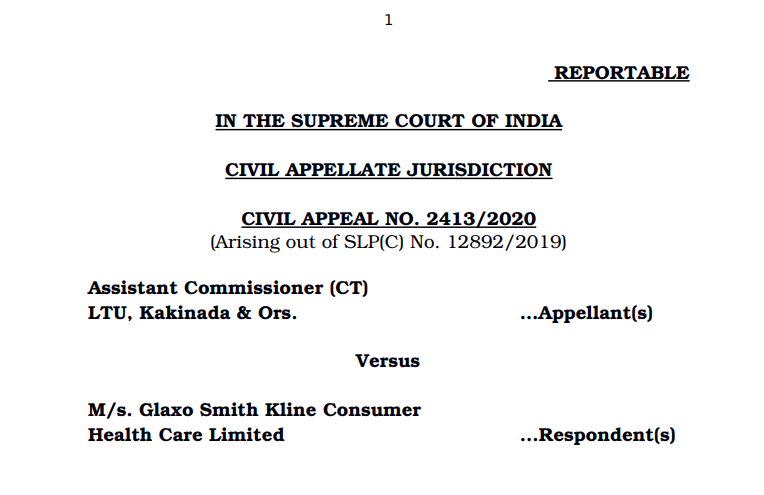

SC in the case of Assistant Commissioner (CT) LTU, Kakinada Versus M/s. Glaxo Smith Kline Consumer Health Care Limited

Citations: Electronics Corporation of India Ltd. vs. Union of India & Ors Baburam Prakash Chandra Maheshwari vs. Antarim Zila Parishad now Zila Parishad, Muzaffarnagar Nivedita Sharma vs. Cellular Operators Association of India & Ors Thansingh Nathmal & Ors. vs. Superintendent of Taxes, Dhubri & Ors. Titaghur Paper Mills Co. Ltd. & Anr. Vs. State of Orissa & Ors Mafatlal Industries Ltd. & Ors. vs. Union of India & Ors. Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited vs. Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Limited & Ors Singh Enterprises vs. Commissioner of Central Excise, Jamshedpur & Ors. Commissioner of Customs and Central Excise vs. Hongo India Private Limited & Anr Chhattisgarh State Electricity Board vs. Central Electricity Regulatory Commission & Ors Suryachakra Power Corporation Limited vs. Electricity Department represented by its Superintending Engineer, Port Blair & Ors. Union Carbide Corpn. v. Union of India State vs. Mushtaq Ahmad & Ors. Panoli Intermediate (India) Pvt. Ltd. vs. Union of India & Ors Phoenix Plasts Company vs. Commissioner of Central Excise (AppealI), Bangalore K.S. Rashid & Son vs. the Income Tax Investigation Commission ITC Ltd. & Anr. Vs. Union of India Raja Mechanical Company Private Limited vs. Commissioner of Central Excise, DelhiI

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL APPELLATE JURISDICTION CIVIL APPEAL NO. 2413/2020 (Arising out of SLP(C) No. 12892/2019) Assistant Commissioner (CT) LTU, Kakinada & Ors. …Appellant(s) Versus M/s. Glaxo Smith Kline Consumer Health Care Limited ...Respondent(s) J U D G M E N T A.M. Khanwilkar, J. 1. Leave granted. 2. The moot question in this appeal emanating from the judgment and order dated 19.11.2018 in Writ Petition No. 39418/2018 passed by the High Court of Judicature at Hyderabad for the State of Telangana and the State of Andhra Pradesh1 is: whether the High Court in exercise of its writ jurisdiction under Article 226 of the Constitution of India ought to entertain a challenge to the assessment order on the soleground that the statutory remedy of appeal against that order stood foreclosed by the law of limitation? 3. The respondent is a registered dealer on the rolls of Assistant Commissioner of Commercial Taxes, Large Tax Payer Unit at Kakinada Division2 under the provisions of Andhra Pradesh Value Added Tax Act, 20053 and the Central Sales Tax Act, 19564 and is engaged in the business of manufacturing and sale of Horlicks, Boost, Biscuits, Ghee, Ayurvedic Medicines etc. The Assistant Commissioner had called upon the respondent to produce books of accounts for the assessment year 201314 for finalisation of assessment under the 1956 Act. The authorised representative of the respondent produced declaration in Form “F” in support of its claim that certain transactions are interState transfers. The information and declaration furnished by the respondent was duly verified and after giving personal hearing to the respondent, final assessment order came to be passed by the Assistant Commissioner on 21.6.2017, raising demand of Rs.76,73,197/ (Rupees seventy six lakhs seventy three thousand one hundred ninety seven only) against turnoverof Rs.3,44,15,240/ (Rupees three crores forty four lakhs fifteen thousand two hundred forty only) on the finding that the respondent had failed to submit Form “F” to the tune of the turnover reported in the Central Sales Tax (CST) return. This assessment order was duly served on the respondent on 22.6.2017. The respondent did not file appeal against this assessment order within the statutory period. Instead, amount equivalent to 12.5% of the demand was deposited on 12.9.2017. The respondent then filed an application under Rule 60 of the Andhra Pradesh Value Added Tax Rules, 20055 , highlighting the error made in raising the demand based on incorrect turnover reported by the respondent. This application was filed only on 8.5.2018, which came to be rejected by the Assistant Commissioner vide order dated 11.5.2018. Aggrieved by the decision dated 11.5.2018, the respondent filed an appeal before the Appellate Deputy Commissioner of Commercial Taxes, Vijayawada6 on 28.5.2018, which came to be rejected on 17.8.2018. It is only thereafter, the respondentassessee was advised to file appeal before the Appellate Deputy Commissioneron 24.9.2018 against the assessment order dated 21.6.2017. In the meantime, another assessment order came to be passed on 31.3.2018 in relation to the Audit taken up for the tax period from 1.4.2013 to 31.3.2017. We are not concerned with the said order in the present appeal. 4. Reverting to the appeal filed by the respondent against the assessment order dated 21.6.2017, the same was dismissed on 25.10.2018 being barred by limitation and also because no sufficient cause was made out. The respondent was then advised to file writ petition before the High Court being Writ Petition No. 39418/2018, solely for quashing and setting aside of assessment order dated 21.6.2017 for tax period – April, 2013 to March, 2014 (CST) being contrary to law, without jurisdiction and in violation of principles of natural justice to the extent of levy on the Branch Transfer turnovers and to direct the Assistant Commissioner (CT) to redo the assessment and reckon the correct Branch Transfer turnover and grant exemption on the basis of Form “F”. The respondent did not challenge the order passed by the Appellate Deputy Commissioner, rejecting the statutory appeal preferred by the respondent against the assessment order dated 21.6.2017,for reasons best known to the respondent. The Division Bench of the High Court, on 8.11.2018, noted that the respondent had already paid 12.5% of the disputed tax, for the purpose of filing an appeal. It also noted the stand taken by the respondent that the employee who was in charge of the tax matters of the respondent, had defaulted and was subsequently suspended in contemplation of disciplinary proceedings, as a result of which statutory appeal could not be filed within the prescribed time. The Division Bench of the High Court directed the respondent to pay an additional amount equivalent to 12.5% of the disputed tax within one week and posted the matter for 19.11.2018. This was an exparte order. The respondent, in terms of the stated order, deposited an additional amount equivalent to 12.5% of the disputed tax amount. The writ petition was then taken up for hearing on 19.11.2018, when after hearing the counsel for the parties, the writ petition came to be allowed and the order passed by the Assistant Commissioner, dated 21.6.2017 has been quashed and set aside and the respondent relegated before the Assistant Commissioner for reconsideration of the matter afresh after giving personal hearing to the respondent to explain the discrepancies. This order has also noted that the respondent hadpaid Rs.9,59,190/ (Rupees nine lakhs fiftynine thousand one hundred ninety only) equivalent to the 12.5% of the taxes in the year 201314 (CST) on 13.11.2018. 5. Feeling aggrieved, the appellants have filed the present appeal. It is urged that the respondent having failed to avail of statutory remedy of appeal within the prescribed time and also because the delay in filing appeal had not been satisfactorily explained, the High Court ought not to have entertained the writ petition at the instance of such person and moreso, because the respondent had allowed the order passed by the appellate authority rejecting the appeal on the ground of delay to become final. In substance, the argument is that the High Court exceeded its jurisdiction and committed manifest error in setting aside the assessment order dated 21.6.2017 passed by the Assistant Commissioner. 6. The respondent, on the other hand, would urge that the High Court has had ample power under Article 226 of the Constitution of India to grant relief to the respondent considering the peculiar facts of the present case being an exceptional situation which if not remedied, would result in failure of justice. 7. We have heard Mr. G.N. Reddy, learned counsel for the appellants and Mr. V. Lakshmikumaran, learned counsel for the respondent. 8. From the indisputable facts, it is evident that the assessment order dated 21.6.2017 was challenged by the respondent by way of statutory appeal before the Appellate Deputy Commissioner only on 24.9.2018. Section 31 of the 2005 Act provides for the statutory remedy against an assessment order. The same, as applicable at the relevant time, reads thus: “31. (1) Any VAT dealer or TOT dealer or any other dealer objecting to any order passed or proceeding recorded by any authority under the provisions of the Act other than an order passed or proceeding recorded by an Additional Commissioner or Joint Commissioner or Deputy Commissioner, may within thirty days from the date on which the order or proceeding was served on him, appeal to such authority as may be prescribed: Provided that the appellate authority may within a further period of thirty days admit the appeal preferred after a period of thirty days if he is satisfied that the VAT dealer or TOT dealer or any other dealer had sufficient cause for not preferring the appeal within that period: Provided further that an appeal so preferred shall not be admitted by the appellate authority concerned unless the dealer produces the proof of payment of tax, penalty, interest or any other amount admitted to be due, or of such instalments as have been granted, and the proof of payment of twelve and half percent of the difference of the tax, penalty, interest or any other amount, assessed by the authority prescribed and the tax, penalty, interest or any other amount admitted by the appellant, for the relevant tax period, in respect of which the appeal is preferred. (2) The appeal shall be in such form, and verified in such manner, as may be prescribed and shall be accompanied by a fee which shall not be less than Rs.50/ (Rupees fifty only) but shall not exceed Rs.1000/ (Rupees one thousand only) as may be prescribed. (3) (a) Where an appeal is admitted under subsection (1), the appellate authority may, on an application filed by the appellant and subject to furnishing of such security or on payment of such part of the disputed tax within such time as may be specified, order stay of collection of balance of the tax under dispute pending disposal of the appeal; (b) Against an order passed by the appellate authority refusing to order stay under clause (a), the appellant may prefer a revision petition within thirty days from the date of the order of such refusal to the Additional Commissioner or the Joint Commissioner who may subject to such terms and conditions as he may think fit, order stay of collection of balance of the tax under dispute pending disposal of the appeal by the appellate authority; (c) Notwithstanding anything in clauses (a) or (b), where a VAT dealer or TOT dealer or any other dealer has preferred an appeal to the Appellate Tribunal under Section 33, the stay, if any, ordered under clause (b) shall be operative till the disposal of the appeal by such Tribunal, and, the stay, if any ordered under clause (a) shall be operative till the disposal of the appeal by such Tribunal, only in case where the Additional Commissioner or the Joint Commissioner on an application made to him by the dealer in the prescribed manner, makes specific order to that effect. (4) The appellate authority may, within a period of two years from the date of admission of such appeal, after giving the appellant an opportunity of being heard and subject to such rules as may be prescribed: (a) confirm, reduce, enhance or annul the assessment or the penalty, or both; or (b) set aside the assessment or penalty, or both, and direct the authority prescribed to pass a fresh order after such further enquiry as may be directed; or (c) pass such other orders as it may think fit. (4A) Where any proceeding under this section has been deferred on account of any stay orders granted by the High Court or Supreme Court in any case or by reason of the fact that an appeal or other proceeding is pending before the High Court or the Supreme Court involving a question of law having a direct bearing on the order or proceeding in question, the period during which the stay order is in force or the period during which such appeal or proceeding is pending, shall be excluded, while computing the period of two years specified in subsection (4) for the purpose of passing appeal order under this section. (5) Before passing orders under subsection (4), the appellate authority may make such enquiry as it deems fit or remand the case to any subordinate officer or authority for an inquiry and report on any specified point or points. (6) Every order passed in appeal under this section shall, subject to the provisions of sections 32, 33, 34 and 35 be final.” Going by the text of this provision, it is evident that the statutory appeal is required to be filed within 30 days from the date on which the order or proceeding was served on the assessee. If the appeal is filed after expiry of prescribed period, the appellate authority is empowered to condone the delay in filing the appeal, only if it is filed within a further period of not exceeding 30 days and sufficient cause for not preferring the appeal within prescribed time is made out. The appellate authority is not empowered to condone delay beyond the aggregate period of 60 days from the date of order or service of proceeding on the assessee, as the case may be. In the present case, admittedly,the appeal was filed way beyond the total 60 days’ period specified in terms of Section 31 of the 2005 Act. In that, the respondent had filed the appeal accompanied by an application for condonation of delay setting out reasons in the following words: “2. It is submitted that the impugned OrderinOriginal dated 21.06.2017 was received by the Applicant on 22.06.2017 and the appeal ought to have been filed by the applicant on 21.07.2017 in terms of section 31 of the Andhra Pradesh VAT Act, 2005. Thus, there is delay in filing the appeal. The Applicants further submits that the delay is not due to any negligence on part of the Applicant. 3. It is submitted that the impugned order was received by Mr. P. Sriram Murthy, but the receipt of this assessment order was not informed to any other person of the company. 4. Mr. P. Sriram Murthy was authorized to handle day to day affairs of sales tax (VAT), service tax and excise and he was also authorized to sign and submit documents with the tax departments, file periodic tax returns and represent the company before Concerned tax authorities. 5. However, the company has alleged Mr. P. Sriram Murthy with committing certain irregularities for past more than 12 months and initiated disciplinary proceedings against him. He has been suspended from his official duties with effect from 26th July 2018. 6. It is only post his suspension that the Applicant came to know about the receipt of impugned order. Also, the Appellant has come to know that Mr. Murthy paid the 12.5% of the demand amount on 12.09.2017 as if it is a regular tax payment. Further, since he did not file the appeal in time, therefore to protect himself from the disciplinary action, he adopted alternate route and filed rectification application under rule 60 which is not permissible under law in case demand has been raised on technical grounds. 7. A separate affidavit as to the facts of the case is also attached herewith. 8. It is stated that in view of the facts and circumstances mentioned above and in the attached affidavit, your honor would appreciate that the delay in filing the appeal is completely unintentional and for the bona fide reasons stated above. The applicant company should not be imposed with tax liabilities due to inaction and malafide intention on one employee. The Applicants further submit that if the delay in filing the above numbered appeal is not condoned, the Applicant would be put to great injustice and irreparable injury. On the other hand, no prejudice would be caused if the delay is condoned. WHEREFORE, it is prayed that the Ld. Appellate Joint Commissioner (ST) be pleased to allow the application for condonation of delay as prayed for.” As stated in the application for condonation of delay in filing the statutory appeal, the respondent caused to file affidavit of Mr. Sreedhar Routh, son of Late Mr. R. Seetha Rama Swamy, who was working as Site Director in the respondent company. In this affidavit, in support of the application for condonation of delay, it is averred thus: “….. That Mr. P. Sriram Murthy, Deputy ManagerFinance, was authorized to handle day to day affairs of sales tax (VAT), service tax and excise. He was also authorized to sign and submit documents with the tax departments, file periodic tax returns and represent the company before concerned tax authorities. that the CST assessment for the period 201314 was completed by the Assistant Commissioner (CT) LTU raising demand of Rs.76,73,197/ vide assessment order dated 21.06.2017. that the assessment order was received by Mr. P. Sriram Murthy. But, the receipt of this assessment order was not informed to any other person of the company. that Mr. P. Sriram Murthy filed application under Rule 60 of the Andhra Pradesh Act, 2005 without informing the company about such filing. that Mr. P. Sriram Murthy also engaged a Chartered Accountant and filed an appeal against rejection of application filed under rule 60. The appointment of Chartered Accountant and filing this appeal was also not informed to the company. that the company has alleged Mr. P. Sriram Murthy with committing certain irregularities and initiated disciplinary proceedings against him. that Mr. P. Sriram Murthy has been suspended from his official duties with effect from 26th July 2018. Investigation in this matter is going on. that it is only post his suspension that we have come to know about the demand of Rs.76,73,197/ lakhs raised vide CST assessment order for the year 20132014 and therefore could not respond or take any action in respect of this order/demand. It is prayed that the Ld. Appellate Joint Commissioner (ST) be pleased to allow the application for condonation of delay as prayed for." The appellate authority vide order dated 25.10.2018, considered the reasons offered by the respondent for the delay in filing of the appeal and concluded that the same were not substantiated with sufficient cause. On that finding including that the delay beyond the period of 60 days from the date of service of the assessment order on the respondentassessee cannot be condoned, the appellate authority observed thus: “However, to abide the principles of natural justice, the appellant has been issued notices dated 03.10.2018 and 19.10.2018 to appear for admission hearings to be held on 10.10.2018 and 25.10.2018 respectively, in the office of Appellate Deputy Commissioner (CT), Vijayawada for explaining reasons and his contentions in support of the admission of appeal petition. The A.R. appeared for the admission hearing on 25.10.2018 and prayed for admission of appeal petition, but not submitted any reliable grounds and substantial documentary evidence in support of their submission that they were unaware of the receipt of original assessment order. It is further pertinent here to record that after receiving the original assessment order, the appellantdealer has filed a request letter before the assessing authority for reassessment under rule 60 of APVAT Rules, 2005. However, the AA has not considered reassessment request, and issued an endorsement dt.11.05.2018, rejecting the reassessment request. The appellant also filed an appeal on such endorsement. That appeal petition based on endorsement has also not been admitted in this office and rejected vide ADC’s orders no. 3470, dt. 17.08.2018. Therefore, cannot be assumed under any circumstances, and by no stretch of imagination that the appellantdealer was not aware of the service of original assessment orders. Hence, it is to be affirmed that the causes putforth for delay condonation are not rational and against the facts of the case. It is also relevant here to state that whatever may be circumstances, the delay beyond 60 days could not be condonable in the hands of the appellate authority, therefore, such request primafacie is not in tune with the provisions of the Act, hence, liable to be rejected. From the aforesaid discussion, it is construed that no favourable grounds can be made to admit the appeal, since the appellant have failed to file appeal petition within the prescribed time under APVAT Act, 2005. It is also pertinent here to note that the Department has duly served the original assessment order to the appellant without any procedural lapse, and also the appellant has admitted that the original orders were received on 22.06.2017. In view of the above, since the appellant failed to prefer an appeal on the original assessment order dated 21.06.2017, which was duly served on the appellant, andas such the original assessment order has become final, and the present appeal filed by the appellant on 24.09.2018 with a delay of 1 year 62 days, hence cannot be admitted. Further the appellants have not submitted any valid reasons/sufficient cause for not preferring the appeal within the prescribed & condonable time of 30+30=60 days of receipt of the original assessment order. Hence the appeal petition is hereby REJECTED as per the provisions of Section 31 of APVAT Act.” (emphasis supplied) The appellate authority was pleased to reject the explanation that the respondent was not aware of the service of assessment order, as it remained unsubstantiated by the respondent. When the matter travelled to the High Court, the Division Bench, after hearing the respondent, proceeded to pass an exparte order on 8.11.2018, which reads thus: “ORDER: It is represented by Mr. S. Dwarakanath, learned counsel for the petitioner that the petitioner has already paid 12.5% of the disputed tax, for the purpose of filing an appeal. But, the employee, who was incharge and who was subsequently, suspended in contemplation of disciplinary proceedings, failed to file the appeal. The contention of the learned counsel for the petitioner is that the issue lies in a narrow campus. Since the petitioner has already paid 12.5% of the disputed tax, the request of the petitioner for granting one more opportunity would be considered favourably, if the petitioner pays an additional amount equivalent to 12.5% of the disputed tax. The petitioner shall make such payment within a period of one week. Post on 19.11.2018 for orders.” Be it noted that the respondent was advised to file writ petition merely for setting aside of the assessment order dated 21.6.2017, presumably, in light of the decision of Full bench of the same High Court in Electronics Corporation of India Ltd. vs. Union of India & Ors 9. We may advert to the assertions made in the writ petition (on the basis of which the High Court was pleased to grant relief to the respondent), to explain the delay in filing of the statutory appeal including the reason why the respondent should be given one opportunity. The same read thus: “….. 7. From the above, it can be summarized that the total disputed demand has arisen on account of two reasons. Firstly, the 1st Respondent has considered the total branch transfer turnover as per monthly CST returns and ignored the revised turnover as per VAT 200B. Even though, the such revised stock transfer value was considered by the 1st Respondent while computing the ITC credit as per rule 20 (8) of AP VAT act. Secondly, receipt of excess forms on account of inclusion of value of freebies, free samples etc. by receiving state while issuing the F Forms. The 1st Respondent treated these excess F Forms value as concealment by the petitioner and levied tax even, on this branch transfer value duly covered by F Forms which is [sic] grossly against the principle of law. 8. It is submitted that the order was served on the petitioner on 22.6.2017 against which, the Petitioner could have preferred appeal before the 2nd Respondent within 30 days from the said date. Unfortunately, no steps were taken to file any appeal within the due date for the reason that the day to day affairs of the Sales Tax,Service Tax and Excise Law was being handled by one Mr. P. Sri Ram Murthy, who was working as Deputy Manager (Finance) in the Company, who failed to take ‘appropriate steps to prefer an appeal within time, by his negligence. Excepting Mr. P. Sri Ram Murthy, there was no other person who was well conversant with the facts and the steps to be taken against the assessment order. The other person Mr. Siddhant Belgaonker, Senior Manager (Finance) who attended the assessment hearing also left the services of the Petitioner on 31.1.2018. Consequently, the assessment order remained uncontested. 9. It is respectfully submitted that apart from this act of negligence, Mr. P. Sri Ram Murthy also committed certain other irregularities over a period of one year, which came to the light of the Management of the Company in the month of July, 2018. Immediately, disciplinary proceedings were initiated against him, by issuing a notice on 26.7.2018 (ex. P3) and also suspending him from official duties with immediate effect. 10. It is submitted that the Petitioner was not aware of the impugned order since that fact was not brought to the notice by its own employee, due to this negligence. 11. It appears, the said Mr. P. Sri Ram Murthy having realized his negligence, made further mistake, by filing an application under Rule 60 of the APVAT Rules read with Rule 14A(10) of the CST (AP) Rules on 9.5.2018 (Ex. P4) contending, interalia, that the revised value of stock transfer as per VAT 200B should have been considered instead of Rs.866,25,15,490/. In the said representation, it is claimed that it has filed revised returns under the VAT Act, disclosing the correct ‘F’ form turnover for the purposes of restricting the input tax credit while filing Form 200B at the end of the year. The ITC credit under VAT was also allowed by the 1st Respondent, considering the stock transfer turnover as Rs.863,33,95,259/. In the said representation, it was contended that the turnover of Rs.1,85,03,360/, could not have been levied with the tax since it is admittedly covered by ‘F’ forms. 12. The representation of the Petitioner under Rule 60 was rejected by the 1st Respondent, by endorsement, dated 11.5.2018 (Ex. P5) on the ground, that it is not a case for considering it as a mistake rectifiable under Rule 60. It is also submitted that Mr. P. Sri Ram Murthyappear to have filed an appeal against the endorsement of the 1st Respondent dated 11.5.2018 to 2nd Respondent on 28.5.2018. This was also without knowledge of the petitioner’s management. 13. It is submitted that the Petitioner was not aware of these developments till the misdeeds of Mr. P. Sri Ram Murthy were being enquired into. It is submitted that Mr. P. Sri Ram Murthy has in fact, remitted an amount of Rs.9,59,150/ being 12.5% of the disputed tax in the assessment order online, on 12.9.2017 (Ex. P6). The payment was made as if it is towards miscellaneous tax payment for June, 2014. When the Petitioner was seeking to reconcile as to how this amount was deposited and under what account it came to known it is for the purpose of preferring an appeal against the impugned order. All this verification happened post suspension of Mr. P. Sri Ram Murthy. 14. The Petitioner faced with this unfortunate situation, filed an appeal under Section 31 of the VAT Act on 24.9.2018 on the bona fide belief that there are good grounds for condonation of the delay since the Petitioner cannot suffer for the errors committed by one of its employees. 15. It is submitted that the 2nd Respondent, vide order, dated 25.10.2018 (Ex. P7), rejected the appeal on the ground that he has no power to condone the delay beyond 30 days. It is also observed in the said order that appeal against the Endorsement was also dismissed by him on 17.8.2018. However, copy of the order is not yet served on the petitioner. The 2nd Respondent observed that the Petitioner cannot dispute the service of assessment order on 22.6.2017 and failure to file the appeal within 60 days would mean that the assessment order has attained finality. 16. The petitioner submits that filing of a further appeal to the APVAT Appellate Tribunal at Visakhapatnam is a futile exercise, since as a creature under the Act, the Tribunal cannot find fault with the 2nd Respondent for not condoning the delay beyond 30 days. 17. The petitioner has lost the appellate remedy by efflux of time. It does not mean that the Petitioner should be left remediless. The petitioner submits that a full Bench of this Hon’ble Court in Electronics Corporation of India Limited (Writ Petition Nos. 9482 and 9485 of 2017,dated 13.3.2018, dealing with similar situation, under Central Excise Act, held that even if the appeal time under the Act has expired, it does not prevent the assessee from preferring a Writ Petition under Article 226 of the Constitution.” 10. The High Court finally allowed the writ petition vide the impugned judgment and order on the ground that the statutory remedy had become ineffective for the respondent (writ petitioner) due to expiry of 60 days from the date of service of the assessment order. Inasmuch as, the appellate authority had no jurisdiction to condone the delay after expiry of 60 days, despite the reason mentioned by the respondent of an extraordinary situation due to the act of commission and omission of its employee who was in charge of the tax matters, forcing the management to suspend him and initiate disciplinary proceedings against him. Soon after becoming aware about the assessment order, the respondent had filed the appeal, but that was after expiry of 60 days’ period. The High Court was also impressed by the contention pressed into service by the respondent that it ought to be given one opportunity to explain to the authority (Assistant Commissioner) about the discrepancies between the value reported in the CST returns and the amount indicated in Form “F” relating to the turnover. The additionalreason as can be discerned from the impugned order is that the respondent had already deposited an additional amount equivalent to 12.5% of the disputed tax amount in terms of the earlier order. We deem it apposite to reproduce the impugned order of the High Court. The same reads thus: “….. The impugned order of assessment is dated 21.6.2017. As against the said order the petitioner filed an appeal with a delay. Since the delay was beyond the period after which it can be condoned, the same was not entertained. Therefore, the petitioner has come up with the above writ petition. The reason stated by the petitioner is that one of the employees who was in charge, indulged in malpractices forcing the management to suspend him and initiate disciplinary proceedings. The petitioner claims that they were not aware of these orders. Therefore, the petitioner seeks one opportunity. The reason why the petitioner seeks one opportunity is that ‘F’ forms submitted by the petitioner were rejected by the Assessing Officer, on the ground that the value of the goods transferred to branch office have not been disclosed in ‘F’ forms. But the claim of the petitioner is that the value was wrongly reported in the CST returns and that the amount indicated in the ‘F’ forms was more than the turnover. Therefore, they seek one opportunity to explain this discrepancy. In view of the peculiar circumstances, even while granting an opportunity to the petitioner, we wanted to put them on condition. Therefore, on 8.11.2018 we passed an interim order to the following effect, “It is represented by Mr. S. Dwarakanath, learned counsel for the petitioner that the petitioner has already paid 12.5% of the disputed tax, for the purpose of filing an appeal. But, the employee, who was incharge and who was subsequently, suspended in contemplation of disciplinary proceedings, failed to file theappeal. The contention of the learned counsel for the petitioner is that the issue lies in a narrow campus. Since the petitioner has already paid 12.5% of the disputed tax, the request of the petitioner for granting one more opportunity would be considered favourably, if the petitioner pays an additional amount equivalent to 12.5% of the disputed tax. The petitioner shall make such payment within a period of one week. Post on 19.11.2018 for orders.” Pursuant to the aforesaid order, the petitioner made payment of Rs.9,59,190/, representing 12.5% of the taxes for the year 20132014 (CST). The amount was paid on 13.11.2018. Therefore, the writ petition is ordered, the impugned order is set aside and the matter is remanded back to the 1 st respondent. The petitioner shall appear before the 1st respondent on 10.12.2018 and explain the discrepancies. After such personal hearing, the 1st respondent may pass orders afresh. As a sequel, pending miscellaneous petitions, if any, shall stand closed. No costs.” 11. In the backdrop of these facts, the central question is: whether the High Court ought to have entertained the writ petition filed by the respondent? As regards the power of the High Court to issue directions, orders or writs in exercise of its jurisdiction under Article 226 of the Constitution of India, the same is no more res integra. Even though the High Court can entertain a writ petition against any order or direction passed/action taken by the State under Article 226 of the Constitution, it ought not to do so as a matter of course when theaggrieved person could have availed of an effective alternative remedy in the manner prescribed by law (see Baburam Prakash Chandra Maheshwari vs. Antarim Zila Parishad now Zila Parishad, Muzaffarnagar8 and also Nivedita Sharma vs. Cellular Operators Association of India & Ors.9 ). In Thansingh Nathmal & Ors. vs. Superintendent of Taxes, Dhubri & Ors.10, the Constitution Bench of this Court made it amply clear that although the power of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution is very wide, the Court must exercise selfimposed restraint and not entertain the writ petition, if an alternative effective remedy is available to the aggrieved person. In paragraph 7, the Court observed thus: “7. Against the order of the Commissioner an order for reference could have been claimed if the appellants satisfied the Commissioner or the High Court that a question of law arose out of the order. But the procedure provided by the Act to invoke the jurisdiction of the High Court was bypassed, the appellants moved the High Court challenging the competence of the Provincial Legislature to extend the concept of sale, and invoked the extraordinary jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226 and sought to reopen the decision of the Taxing Authorities on question of fact. The jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution is couched in wide terms and the exercise thereof is not subject to any restrictions except the territorial restrictions which are expressly provided in the Articles.But the exercise of the jurisdiction is discretionary: it is not exercised merely because it is lawful to do so. The very amplitude of the jurisdiction demands that it will ordinarily be exercised subject to certain selfimposed limitations. Resort that jurisdiction is not intended as an alternative remedy for relief which may be obtained in a suit or other mode prescribed by statute. Ordinarily the Court will not entertain a petition for a writ under Article 226, where the petitioner has an alternative remedy, which without being unduly onerous, provides an equally efficacious remedy. Again the High Court does not generally enter upon a determination of questions which demand an elaborate examination of evidence to establish the right to enforce which the writ is claimed. The High Court does not therefore act as a court of appeal against the decision of a court or tribunal, to correct errors of fact, and does not by assuming jurisdiction under Article 226 trench upon an alternative remedy provided by statute for obtaining relief. Where it is open to the aggrieved petitioner to move another tribunal, or even itself in another jurisdiction for obtaining redress in the manner provided by a statute, the High Court normally will not permit by entertaining a petition under Article 226 of the Constitution the machinery created under the statute to be bypassed, and will leave the party applying to it to seek resort to the machinery so set up.” (emphasis supplied) We may usefully refer to the exposition of this Court in Titaghur Paper Mills Co. Ltd. & Anr. Vs. State of Orissa & Ors.11 , wherein it is observed that where a right or liability is created by a statute, which gives a special remedy for enforcing it, the remedy provided by that statute must only be availed of. In paragraph 11, the Court observed thus: “11. Under the scheme of the Act, there is a hierarchy of authorities before which the petitioners can get adequate redress against the wrongful acts complained of. The petitioners have the right to prefer an appeal before the Prescribed Authority under subsection (1) of Section 23 of the Act. If the petitioners are dissatisfied with the decision in the appeal, they can prefer a further appeal to the Tribunal under subsection (3) of Section 23 of the Act, and then ask for a case to be stated upon a question of law for the opinion of the High Court under Section 24 of the Act. The Act provides for a complete machinery to challenge an order of assessment, and the impugned orders of assessment can only be challenged by the mode prescribed by the Act and not by a petition under Article 226 of the Constitution. It is now well recognised that where a right or liability is created by a statute which gives a special remedy for enforcing it, the remedy provided by that statute only must be availed of. This rule was stated with great clarity by Willes, J. in Wolverhampton New Waterworks Co. v. Hawkesford [(1859) 6 CBNS 336, 356] in the following passage: There are three classes of cases in which a liability may be established founded upon statute. . . . But there is a third class, viz. where a liability not existing at common law is created by a statute which at the same time gives a special and particular remedy for enforcing it…. The remedy provided by the statute must be followed, and it is not competent to the party to pursue the course applicable to cases of the second class. The form given by the statute must be adopted and adhered to. The rule laid down in this passage was approved by the House of Lords in Neville v. London Express Newspapers Ltd. (1919 AC 368) and has been reaffirmed by the Privy Council in AttorneyGeneral of Trinidad and Tobago v. Gordon Grant & Co. Ltd. (1935 AC 532) and Secretary of State v. Mask & Co. (AIR 1940 PC 105). It has also been held to be equally applicable to enforcement of rights, and has been followed by this Court throughout. The High Court was therefore justified in dismissing the writ petitions in limine.” In the subsequent decision in Mafatlal Industries Ltd. & Ors. vs. Union of India & Ors.12, this Court went on to observe that an Act cannot bar and curtail remedy under Article 226 or 32 of the Constitution. The Court, however, added a word of caution and expounded that the constitutional Court would certainly take note of the legislative intent manifested in the provisions of the Act and would exercise its jurisdiction consistent with the provisions of the enactment. To put it differently, the fact that the High Court has wide jurisdiction under Article 226 of the Constitution, does not mean that it can disregard the substantive provisions of a statute and pass orders which can be settled only through a mechanism prescribed by the statute. 12. Indubitably, the powers of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution are wide, but certainly not wider than the plenary powers bestowed on this Court under Article 142 of the Constitution. Article 142 is a conglomeration and repository of the entire judicial powers under the Constitution, to do complete justice to the parties. Even while exercising that power, this Court is required to bear in mind the legislative intent and not torender the statutory provision otiose. In a recent decision of a threeJudge Bench of this Court in Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited vs. Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Limited & Ors.13, the statutory appeal filed before this Court was barred by 71 days and the maximum time limit for condoning the delay in terms of Section 125 of the Electricity Act, 2003 was only 60 days. In other words, the appeal was presented beyond the condonable period of 60 days. As a result, this Court could not have condoned the delay of 71 days. Notably, while admitting the appeal, the Court had condoned the delay in filing the appeal. However, at the final hearing of the appeal, an objection regarding appeal being barred by limitation was allowed to be raised being a jurisdictional issue and while dealing with the said objection, the Court referred to the decisions in Singh Enterprises vs. Commissioner of Central Excise, Jamshedpur & Ors.14, Commissioner of Customs and Central Excise vs. Hongo India Private Limited & Anr.15 , Chhattisgarh State Electricity Board vs. Central ElectricityRegulatory Commission & Ors.16 and Suryachakra Power Corporation Limited vs. Electricity Department represented by its Superintending Engineer, Port Blair & Ors.17 and concluded that Section 5 of the Limitation Act, 1963 cannot be invoked by the Court for maintaining an appeal beyond maximum prescribed period in Section 125 of the Electricity Act. 13. The principle underlying the dictum in this decision would apply proprio vigore to Section 31 of the 2005 Act including to the powers of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution. Notably, in this decision, a submission was canvassed by the assessee that in the peculiar facts of that case (as urged in the present case), the Court may exercise its jurisdiction under Article 142 of the Constitution, so that complete justice can be done. This argument has been considered and plainly rejected in the following words: “12. In A.R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak, (1988) 2 SCC 602, while explicating and elaborating the principles under Article 142, Sabyasachi Mukharji, J. (as his Lordship then was) opined thus: (SCC p. 656, para 50) “50. … The fact that the rule was discretionary did not alter the position. Though Article 142(1) empowers the Supreme Court to pass any order to do complete justice between the parties, thecourt cannot make an order inconsistent with the fundamental rights guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution. No question of inconsistency between Article 142(1) and Article 32 arose. Gajendragadkar, J., speaking [Prem Chand Garg v. Excise Commr., AIR 1963 SC 996] for the majority of the Judges of this Court said that Article 142(1) did not confer any power on this Court to contravene the provisions of Article 32 of the Constitution. Nor did Article 145 confer power upon this Court to make rules, empowering it to contravene the provisions of the fundamental right. At AIR pp. 100203, para 12 : SCR p. 899 of the Report, Gajendragadkar, J., reiterated that the powers of this Court are no doubt very wide and they are intended and “will always be exercised in the interests of justice”. But that is not to say that an order can be made by this Court which is inconsistent with the fundamental rights guaranteed by Part III of the Constitution. It was emphasised that an order which this Court could make in order to do complete justice between the parties, must not only be consistent with the fundamental rights guaranteed by the Constitution, but it cannot even be inconsistent with the substantive provisions of the relevant statutory laws. The court therefore, held that it was not possible to hold that Article 142(1) conferred upon this Court powers which could contravene the provisions of Article 32.” (emphasis in original) 13. The said decision has been clarified by a Constitution Bench in Union Carbide Corpn. v. Union of India, (1991) 4 SCC 584, wherein M.N. Venkatachaliah, J. (as his Lordship then was) speaking for the majority, ruled that: (SCC pp. 63435, para 83) “83. It is necessary to set at rest certain misconceptions in the arguments touching the scope of the powers of this Court under Article 142(1) of the Constitution. These issues are matters of serious public importance. The proposition that a provision in any ordinary law irrespective of the importance of the public policy on which it is founded, operates to limitthe powers of the Apex Court under Article 142(1) is unsound and erroneous. In both Prem Chand Garg v. Excise Commr., AIR 1963 SC 996, as well as A.R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak, (1988) 2 SCC 602, cases the point was one of violation of constitutional provisions and constitutional rights. The observations as to the effect of inconsistency with statutory provisions were really unnecessary in those cases as the decisions in the ultimate analysis turned on the breach of constitutional rights. We agree with Shri Nariman that the power of the Court under Article 142 insofar as quashing of criminal proceedings are concerned is not exhausted by Section 320 or 321 or 482 CrPC or all of them put together. The power under Article 142 is at an entirely different level and of a different quality. Prohibitions or limitations or provisions contained in ordinary laws cannot, ipso facto, act as prohibitions or limitations on the constitutional powers under Article 142. Such prohibitions or limitations in the statutes might embody and reflect the scheme of a particular law, taking into account the nature and status of the authority or the court on which conferment of powers — limited in some appropriate way — is contemplated. The limitations may not necessarily reflect or be based on any fundamental considerations of public policy. Shri Sorabjee, learned Attorney General, referring to Garg case [Prem Chand Garg v. Excise Commr., AIR 1963 SC 996], said that limitation on the powers under Article 142 arising from “inconsistency with express statutory provisions of substantive law” must really mean and be understood as some express prohibition contained in any substantive statutory law. He suggested that if the expression “prohibition” is read in place of “provision” that would perhaps convey the appropriate idea. But we think that such prohibition should also be shown to be based on some underlying fundamental and general issues of public policy and not merely incidental to a particular statutory scheme or pattern. It will again be wholly incorrect to say that powers under Article 142 are subject to such expressstatutory prohibitions. That would convey the idea that statutory provisions override a constitutional provision. Perhaps, the proper way of expressing the idea is that in exercising powers under Article 142 and in assessing the needs of “complete justice” of a cause or matter, the Apex Court will take note of the express prohibitions in any substantive statutory provision based on some fundamental principles of public policy and regulate the exercise of its power and discretion accordingly. The proposition does not relate to the powers of the Court under Article 142, but only to what is or is not “complete justice” of a cause or matter and in the ultimate analysis of the propriety of the exercise of the power. No question of lack of jurisdiction or of nullity can arise.” (emphasis in original) 14. In this regard, another Constitution Bench in Supreme Court Bar Assn. v. Union of India, (1998) 4 SCC 409] opined: (SCC pp. 43738, para 56) “56. As a matter of fact, the observations on which emphasis has been placed by us from the Union Carbide case [Union Carbide Corpn. v. Union of India, (1991) 4 SCC 584], A.R. Antulay case [A.R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak, (1988) 2 SCC 602] and Delhi Judicial Service Assn. v. State of Gujarat, (1991) 4 SCC 406, go to show that they do not strictly speaking come into any conflict with the observations of the majority made in Prem Chand Garg case [Prem Chand Garg v. Excise Commr., AIR 1963 SC 996]. It is one thing to say that “prohibitions or limitations in a statute” cannot come in the way of exercise of jurisdiction under Article 142 to do complete justice between the parties in the pending “cause or matter” arising out of that statute, but quite a different thing to say that while exercising jurisdiction under Article 142, this Court can altogether ignore the substantive provisions of a statute, dealing with the subject and pass orders concerning an issue which can be settled only through a mechanism prescribedin another statute. This Court did not say so in Union Carbide case [Union Carbide Corpn. v. Union of India, (1991) 4 SCC 584] either expressly or by implication and on the contrary it has been held that the Apex Court will take note of the express provisions of any substantive statutory law and regulate the exercise of its power and discretion accordingly. …” (emphasis in original) 15. From the aforesaid decisions, it is clear as crystal that the Constitution Bench in Supreme Court Bar Assn. v. Union of India, (1998) 4 SCC 409, has ruled that there is no conflict of opinion in Antulay case [A.R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak, (1988) 2 SCC 602] or in Union Carbide Corpn. case [Union Carbide Corpn. v. Union of India, (1991) 4 SCC 584] with the principle set down in Prem Chand Garg v. Excise Commr., AIR 1963 SC 996. Be it noted, when there is a statutory command by the legislation as regards limitation and there is the postulate that delay can be condoned for a further period not exceeding sixty days, needless to say, it is based on certain underlined, fundamental, general issues of public policy as has been held in Union Carbide Corpn. case [Union Carbide Corpn. v. Union of India, (1991) 4 SCC 584]. As the pronouncement in Chhattisgarh SEB v. Central Electricity Regulatory Commission, (2010) 5 SCC 23, lays down quite clearly that the policy behind the Act emphasising on the constitution of a special adjudicatory forum, is meant to expeditiously decide the grievances of a person who may be aggrieved by an order of the adjudicatory officer or by an appropriate Commission. The Act is a special legislation within the meaning of Section 29(2) of the Limitation Act and, therefore, the prescription with regard to the limitation has to be the binding effect and the same has to be followed regard being had to its mandatory nature. To put it in a different way, the prescription of limitation in a case of present nature, when the statute commands that this Court may condone the further delay not beyond 60 days, it would come within the ambit and sweep of the provisions and policy of legislation. It is equivalent to Section 3 of the Limitation Act. Therefore, it isuncondonable and it cannot be condoned taking recourse to Article 142 of the Constitution. 16. We had stated earlier that we will be adverting to the passage in Suryachakra Power Corpn. Ltd. v. Electricity Deptt., (2016) 16 SCC 152. There, the Court had referred to Section 14 of the Limitation Act. It fundamentally relied on M.P. Steel Corpn. v. CCE, (2015) 7 SCC 58, wherein the Court after referring to certain authorities, analysed thus: (M.P. Steel Corpn. Case), SCC p. 91, para 43) “43. … when a certain period is excluded by applying the principles contained in Section 14, there is no delay to be attributed to the appellant and the limitation period provided by the statute concerned continues to be the stated period and not more than the stated period. We conclude, therefore, that the principle of Section 14 which is a principle based on advancing the cause of justice would certainly apply to exclude time taken in prosecuting proceedings which are bona fide and with due diligence pursued, which ultimately end without a decision on the merits of the case.”” (emphasis in italics – in original, and in bold – supplied) Similarly, in State vs. Mushtaq Ahmad & Ors.18, this Court opined that where minimum sentence is provided for an offence then no Court can impose lesser punishment on ground of mitigating factors. 14. A priori, we have no hesitation in taking the view that what this Court cannot do in exercise of its plenary powers under Article 142 of the Constitution, it is unfathomable as to how the High Court can take a different approach in the matter inreference to Article 226 of the Constitution. The principle underlying the rejection of such argument by this Court would apply on all fours to the exercise of power by the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution. 15. We may now revert to the Full Bench decision of the Andhra Pradesh High Court in Electronics Corporation of India Ltd. (supra), which had adopted the view taken by the Full Bench of the Gujarat High Court in Panoli Intermediate (India) Pvt. Ltd. vs. Union of India & Ors.19 and also of the Karnataka High Court in Phoenix Plasts Company vs. Commissioner of Central Excise (AppealI), Bangalore20. The logic applied in these decisions proceeds on fallacious premise. For, these decisions are premised on the logic that provision such as Section 31 of the 1995 Act, cannot curtail the jurisdiction of the High Court under Articles 226 and 227 of the Constitution. This approach is faulty. It is not a matter of taking away the jurisdiction of the High Court. In a given case, the assessee may approach the High Court before the statutory period of appeal expires to challenge the assessment order by way of writ petitionon the ground that the same is without jurisdiction or passed in excess of jurisdiction by overstepping or crossing the limits of jurisdiction including in flagrant disregard of law and rules of procedure or in violation of principles of natural justice, where no procedure is specified. The High Court may accede to such a challenge and can also nonsuit the petitioner on the ground that alternative efficacious remedy is available and that be invoked by the writ petitioner. However, if the writ petitioner choses to approach the High Court after expiry of the maximum limitation period of 60 days prescribed under Section 31 of the 2005 Act, the High Court cannot disregard the statutory period for redressal of the grievance and entertain the writ petition of such a party as a matter of course. Doing so would be in the teeth of the principle underlying the dictum of a threeJudge Bench of this Court in Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited (supra). In other words, the fact that the High Court has wide powers, does not mean that it would issue a writ which may be inconsistent with the legislative intent regarding the dispensation explicitly prescribed under Section 31 of the 2005 Act. That would render the legislative scheme and intention behind the stated provision otiose. 16. The respondent had relied on the decision of this Court in K.S. Rashid & Son vs. the Income Tax Investigation Commission21. This decision of the Constitution Bench, no doubt, deals with the extent of power of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution and the situation when the High Court can refuse to exercise its discretion, such as when alternative efficacious remedy is available to the aggrieved party. In paragraph 4 (last paragraph) of this decision, however, the Court plainly noted that it was not necessary to express any final opinion on the question as to whether Section 8(5) of the Taxation on Income (Investigation Commission) Act, 1947 (Act XXX of 1947) is to be regarded as providing the only remedy available to the aggrieved party and that it excludes altogether the remedy provided for under Article 226 of the Constitution. 17. Reliance was then placed on a threeJudge Bench decision of this Court in ITC Ltd. & Anr. Vs. Union of India22. In that case, the High Court had dismissed the writ petition on the ground that the petitioner therein had an adequate alternative remedy by way of an appeal under Section 35 of the CentralExcise Act. Concededly, this Court was pleased to uphold that opinion of the High Court. However, whilst considering the difficulty expressed by the petitioner therein that the statutory remedy of appeal had now become time barred during the pendency of the proceedings before the High Court and before this Court, the Court permitted the petitioner therein to resort to remedy of statutory appeal and directed the appellate authority to decide the appeal on merits. This obviously was done on the basis of concession given by the counsel appearing for the Revenue as noted in paragraph 2(1) of the order, which reads thus: “2. The High Court has dismissed the writ petition filed by the petitioner on the ground that there is an adequate alternative remedy by way of an appeal under Section 35 of the Central Excise Act. Learned counsel for the petitioner submits that the petitioner will face certain difficulties in pursuing this remedy: (1) This remedy may not be any longer available to it because the appeal has to be filed within a period of three months from the date of the assessment order and delay can be condoned only to the extent of three more months by the Collector under Section 35 of the Act. It is pointed out that the petitioner did not file an appeal because the Collector (Appeal) at Madras had taken a view in a similar matter that an appeal was not maintainable. That apart, the petitioner in view of the huge demand involved filed a writ petition and so did not file an appeal. In the circumstances of the case, we are of the opinion that the ends of justice will be met if we permit the petitioner to file abelated appeal within one month from today with an application for condonation of delay, whereon the appeal may be entertained. Learned counsel for the Revenue has stated before us that the Revenue will not object to the entertainment of the appeal on the ground that it is barred by time. In view of this direction and concession, the petitioner will have an effective alternative remedy by way of an appeal. (emphasis supplied) In that case, it appears that the writ petition was filed within statutory period and legal remedy was being pursued in good faith by the assessee (appellant). 18. Suffice it to observe that this decision is on the facts of that case and cannot be cited as a precedent in support of an argument that the High Court is free to entertain the writ petition assailing the assessment order even if filed beyond the statutory period of maximum 60 days in filing appeal. The remedy of appeal is creature of statute. If the appeal is presented by the assessee beyond the extended statutory limitation period of 60 days in terms of Section 31 of the 2005 Act and is, therefore, not entertained, it is incomprehensible as to how it would become a case of violation of fundamental right, much less statutory or legal right as such. 19. Arguendo, reverting to the factual matrix of the present case, it is noticed that the respondent had asserted that it was not aware about the passing of assessment order dated 21.6.2017 although it is admitted that the same was served on the authorised representative of the respondent on 22.6.2017. The date on which the respondent became aware about the order is not expressly stated either in the application for condonation of delay filed before the appellate authority, the affidavit filed in support of the said application or for that matter, in the memo of writ petition. On the other hand, it is seen that the amount equivalent to 12.5% of the tax amount came to be deposited on 12.9.2017 for and on behalf of respondent, without filing an appeal and without any demur after the expiry of statutory period of maximum 60 days, prescribed under Section 31 of the 2005 Act. Not only that, the respondent filed a formal application under Rule 60 of the 2005 Rules on 8.5.2018 and pursued the same in appeal, which was rejected on 17.8.2018. Furthermore, the appeal in question against the assessment order came to be filed only on 24.9.2018 without disclosing the date on which the respondent in fact became aware about the existence of the assessment order dated 21.6.2017. On the other hand, in the affidavit of Mr. Sreedhar Routh, Site Director of the respondentcompany (filed in support of the application for condonation of delay before the appellate authority), it is stated that the company became aware about the irregularities committed by its erring official (Mr. P. Sriram Murthy) in the month of July, 2018, which presupposes that the respondent must have become aware about the assessment order, at least in July, 2018. In the same affidavit, it is asserted that the respondent company was not aware about the assessment order, as it was not brought to its notice by the employee concerned due to his negligence. The respondent in the writ petition has averred that the appeal was rejected by the appellate authority on the ground that it had no power to condone the delay beyond 30 days, when in fact, the order examines the cause set out by the respondent and concludes that the same was unsubstantiated by the respondent. That finding has not been examined by the High Court in the impugned judgment and order at all, but the High Court was more impressed by the fact that the respondent was in a position to offer some explanation about the discrepancies in respect of the volume of turnover and that the respondent had already deposited 12.5% of the additional amount in terms of the previous order passed by it. That reason can have no bearing on the justification for nonfiling of the appeal within the statutoryperiod. Notably, the respondent had relied on the affidavit of the Site Director and no affidavit of the concerned employee (P. Sriram Murthy, Deputy ManagerFinance) or at least the other employee [Siddhant Belgaonker, Senior Manager (Finance)], who was associated with the erring employee during the relevant period, has been filed in support of the stand taken in the application for condonation of delay. Pertinently, no finding has been recorded by the High Court that it was a case of violation of principles of natural justice or noncompliance of statutory requirements in any manner. Be that as it may, since the statutory period specified for filing of appeal had expired long back in August, 2017 itself and the appeal came to be filed by the respondent only on 24.9.2018, without substantiating the plea about inability to file appeal within the prescribed time, no indulgence could be shown to the respondent at all. 20. Reverting to the contention that the respondent having failed to assail the order passed by the appellate authority, dated 25.10.2018 rejecting the application for condonation of delay, the assessment order passed by the Assistant Commissioner, dated 21.6.2017 stood merged, need not detain us in view of the exposition of this Court in Raja Mechanical Company PrivateLimited vs. Commissioner of Central Excise, DelhiI23. It is well settled that rejection of delay application by the appellate forum does not entail in merger of the assessment order with that order. 21. Taking any view of the matter, therefore, the High Court ought not to have entertained the subject writ petition filed by the respondent herein. The same deserved to be rejected at the threshold. 22. Accordingly, we allow this appeal and set aside the impugned judgment and order passed by the High Court and dismiss the writ petition. There shall be no order as to costs. Pending interlocutory applications, if any, shall stand disposed of. Download the copy:

ConsultEase Administrator

ConsultEase Administrator

Consultant

Faridabad, India

As a Consultease Administrator, I'm responsible for the smooth administration of our portal. Reach out to me in case you need help.