Kerala HC in the case of Abbott Healthcare Private Limited

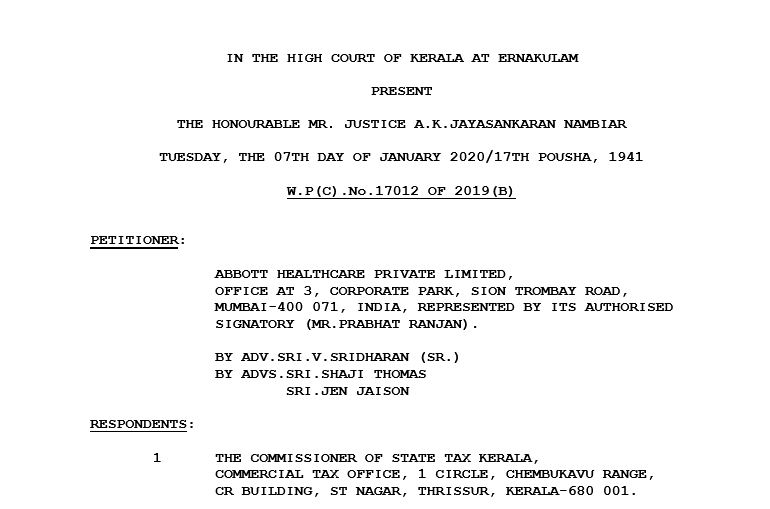

Citations: Nell Gwynn House Maintenance Fund Trustees v. Customs and Excise Commissioners Telewest Communications PLC v. Customs and Excise Commissioners IN THE HIGH COURT OF KERALA AT ERNAKULAM PRESENT THE HONOURABLE MR. JUSTICE A.K.JAYASANKARAN NAMBIAR TUESDAY, THE 07TH DAY OF JANUARY 2020/17TH POUSHA, 1941 W.P(C).No.17012 OF 2019(B) PETITIONER: ABBOTT HEALTHCARE PRIVATE LIMITED, OFFICE AT 3, CORPORATE PARK, SION TROMBAY ROAD, MUMBAI-400 071, INDIA, REPRESENTED BY ITS AUTHORISED SIGNATORY (MR.PRABHAT RANJAN). BY ADV.SRI.V.SRIDHARAN (SR.) BY ADVS.SRI.SHAJI THOMAS SRI.JEN JAISON RESPONDENTS: 1 THE COMMISSIONER OF STATE TAX KERALA, COMMERCIAL TAX OFFICE, 1 CIRCLE, CHEMBUKAVU RANGE, CR BUILDING, ST NAGAR, THRISSUR, KERALA-680 001. 2 THE COMMISSIONER, CGST, KERALA, COMMERCIAL TAX OFFICE, 1 CIRCLE, CHEMBUKAVU RANGE, CR BUILDING, ST NAGAR, THRISSUR, KERALA-680 001. 3 UNION OF INDIA, REPRESENTED BY ITS REVENUE SECRETARY, DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE, MINISTRY OF FINANCE, 128-A/NORTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI-110 001. 4 STATE OF KERALA, REPRESENTED BY ITS SECRETARY TO TAX DEPARTMENT, GOVERNMENT OF KERALA, SECRETARIAT, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM-695 001. 5 THE KERALA AUTHORITY FOR ADVANCE RULING, TAX TOWER, KILLIPPALAM, KARAMANA P.O., THIRUVANANTHAPURAM, KERALA-695 002. 6 THE KERALA APPELLATE AUTHORITY FOR ADVANCE RULING, THIRUVANANTHAPURAM ZONE, CENTRAL REVENUE BUILDING, I.S.PRESS ROAD, KOCHI, KERALA-682 018. R1 BY SMT.DR.THUSHARA JAMES, GOVERNMENT PLEADER R3 BY SMT.MAHESWARY.G., CGC THIS WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) HAVING BEEN FINALLY HEARD ON 07.12.2019, THE COURT ON 07.01.2020 DELIVERED THE FOLLOWING:

J U D G M E N T The petitioner herein is a company incorporated under the Companies Act, 1956, having its registered office in Mumbai. It is engaged inter alia in the sale of pharmaceutical products, diagnostic kits etc. and it is registered under the Goods andServices Tax Act in the State of Kerala. It is the case of the petitioner in the writ petition that as per the business model operated by it in the State of Kerala, it places its diagnostic instruments at the premises of unrelated hospitals, laboratories etc. for their use for a specified period without any consideration. The petitioner also enters into Reagent Supply and Instrument Use Agreements with various hospitals, laboratories etc, whereunder, the arrangement between the parties is for the supply of medical instruments to the hospital/laboratory concerned, for their use, without any consideration for a specified period and for the supply of specified quantities ofreagents, calibrators, disposables etc. at the prices specified in the agreement, through its distributors on payment of applicable GST. It is stated that, as per the agreement, while the supply of instruments is by the petitioner, the supply of reagents, calibrators and disposables are effected by its distributor,who purchases the said products from the petitioner on principal to principal basis. When the distributor supplies the reagents, calibrators and disposables to the hospitals/laboratories concerned, the distributor discharges the applicable GST on the price charged for supply of the said products. In other words, there is no direct sale/supply of the reagents, calibrators and disposables by the petitioner to the hospitals/laboratories in question. It is also stated that the value of instruments placed at the premises of the hospitals/laboratories compared to the total turnover of supply of reagents, calibrators and disposables by the distributor over the contract period, is small and would only be around 20% of the turnover of supply of reagents, calibrators etc. The agreement entered into between the parties also contains a clause which provides that if the hospital fails to purchase specified minimumquantum of reagents, calibrators etc., then the petitioner is entitled to recover from the hospital an amount equal to the deficit in the actual purchases, vis-a-vis, the minimum purchase stipulated under the contract.

2. It would appear that when a consignment of instruments was being transported to a laboratory without any consideration, pursuant to the agreement entered into between the parties, the same was seized by the Assistant State Tax Officer, Kozhikode, on the ground that the goods were not accompanied with a tax invoice but were being transported under a delivery challan. Although the detained goods were subsequently released consequent to the petitioner furnishing a bank guarantee and a bond as provided under the CGST Act and Rules, the petitioner thought it appropriate to obtain an Advance Ruling from the Authority for Advance Ruling [hereinafter referred to as the “AAR”], the 5th respondent herein, on the following question: “Whether in the facts of the present case, the provision of specified medical instruments by the Applicant to unrelated parties like hospital(s), Lab (s), for use without any consideration, constitutes a “supply” or whether it constitutes “movement of goods otherwise than by way of supply” as per provisions of the CGST/SGST Act, 2017?” The AAR, by Ext.P2 order dated 26.09.2018, held that the placement of specified medical instruments to unrelated customers like hospitals, laboratories etc., for their use without any consideration, in the backdrop of an agreement containing minimum purchase obligation of products like reagents, calibrators, disposables etc. for a specified period constituted a “composite supply”. It thereafter found that the principal supply in the said composite supply was of the transfer of right to use goods for any purpose which was liable to GST under Sl.No.17(iii) – Heading 9973 of Notification No.11/2017 Central Tax (Rate) dated 28.06.2017. As a consequence of the said Ruling, the supply of reagents, calibrators, disposables etc., which is otherwise taxable @ 5% [2.5% CGST + 2.5% SGST], became taxable at the rate of tax applicable to the instruments, namely, 18% [9% CGST + 9% SGST]. 3. Aggrieved by the said order of the AAR, the petitioner preferred an appeal before the Appellate Authority, the 6th respondent in the writ petition. The said appeal, however, was rejected by the 6th respondent, who confirmed the order of the AAR, by Ext.P1 order. In the writ petition, Exts.P1 and P2 orders are impugned inter alia on the contention that, while the 5th and 6th respondents erred in rendering a finding as regards composite supply, when the said query was not raised before them for clarification, the said finding itself was illegal and against the provisions of the CGST/SGST Act. 4. Appearing for the petitioner, the learned senior counsel Sri. V. Sridharan assisted by Adv. Sri.Shaji Thomas, would contend as follows: ● The 5th and 6th respondents decided an issue that was not referred to them for their ruling. The said respondents therefore acted without jurisdiction in rendering their findings on the issue relating to composite supply. ● The finding that the supplies effected by the petitioner constituted a composite supply of medical equipments together with reagents, calibrators and disposables, is a perverse one because it is not based on any material and is purely based on a presumption and supposition divorced from reality. ● The supply effected by the petitioner is of an instrument which is independent and distinct from the supply of reagents, calibrators and disposables by the distributor, and hence, the two supplies have to be treated as independent, and not as a composite supply. ● At any rate, the supply of the instrument cannot be seen as the principal supply in a deemed composite supply, since the value of the instrument supplied during the contract period constitute only about 20% of the value of the reagents/calibrators/disposables supplied during the same contract period. 5. Per contra, the learned Government Pleader Smt.Thushara James would respond to the submission of the learned senior counsel for the petitioner as follows: ● To answer the issue raised by the petitioner, the AAR had to look at the supply effected by the petitioner in the backdrop of the contractual terms under which the supply was effected. When so viewed, it is apparent that the instrument supplied by the petitioner cannot function without the reagent/calibrator/disposables supplied by the distributor of the petitioner. It followed therefore that the functioning of the instrument was dependant on the reagents/calibrators/disposables supplied by the distributor, and hence, the supplies effected by both persons had to be clubbed to ascertain the real “supply” that was effected by the petitioner. ● When both the supplies are taken together as envisaged under the contract entered into between the parties, then the supply effected by the petitioner has to be seen as a composite supply, with the instrument being the principal supply, and the reagents constituting the incidental supply. The rate of tax applicable to the instrument had therefore to be applied to the supply of reagents/calibrators/disposables. 6. I have considered the pleadings in this case as also the rival submissions. To appreciate the challenge in the writ petition, to the orders of the AAR and the Appellate Authority, one has to first notice the query that was raised by the petitioner before the AAR under Section 99 of the GST Act. The said query reads as follows: “Whether in the facts of the present case, the provision of specified medical instruments by the Applicant to unrelated parties like hospital(s), Lab (s), for uses without any consideration, constitutes a “supply” or whether it constitutes “movement of goods otherwise than by way of supply” as per provisions of the CGST/SGST Act, 2017?” The AAR examined the query in the backdrop of the agreement entered into between the petitioner and the hospitals/laboratories concerned, and opined that the petitioner was effecting two supplies, namely, of medical instruments and of reagents/calibrators/disposables to be used along with the instrument. Since the instrument supplied had no utility to the customer unless he also bought the reagents/calibrators/disposables, the supply of the instrument and the reagents etc. had to be seen as naturally bundled to form a composite supply. The AAR went on to observe that the supply of the instrument was to be treated as the principal supply, in the said composite supply, and accordingly, that the reagents, calibrators and disposables had to be taxed at the higher rate applicable to the instrument supplied. The arrangement of supplies by the petitioner through the agreement was seen as a scheme to avoid payment of tax at higher rate. As regards valuation of the said supply, the AAR found that in terms of the agreement, the petitioner had, in fact, supplied the medical instrument for deferred consideration since, according to it, the minimum purchase obligation in respect of reagents etc., under the agreement, ensured that the overall price realised from the customer subsumed within it, the rent for the instrument as well. This was more so because, the agreement between the parties clearly stipulated that if the required quantity of consumables was not purchased by the customer hospital, it was obliged to pay the petitioner the deficit amount. The aforesaid findings of the AAR were upheld by the Appellate Authority as well. 7. On a consideration of the facts and circumstances of the case and the reasonings of the AAR and the Appellate Authority, it is my view that while it may have been open to the AAR to enquire, based on the terms of the agreement, whether the supply of the medical instruments to the customer, although styled as a free supply, was in fact one for valid consideration, its findings as regards a composite supply are wholly without jurisdiction. It is apparent that the AAR went beyond the terms of reference in embarking upon an enquiry as to whether the supplies effected under the agreement between the petitioner and the customer hospitals/laboratories, constituted a composite supply. As a consequence, the AAR did not go into the real issue of whether the supply of instruments per se constituted a taxable supply under the CGST Act. While these facts would have sufficed for this Court to remit the matter to the AAR for a fresh consideration of the issue, the learned senior counsel would urge me to give a definite view on the correctness of the finding of the AAR regarding the transaction being a composite supply. It is therefore that I deem it appropriate to offer my view on the said finding of the AAR, while relegating the matter back to the AAR for a fresh consideration of the query referred to it, for its clarification. 8. When I examine the order of the AAR, in the backdrop of the query that was raised before it for its clarification, I find that there was no occasion for the AAR to go into the issue of whether the supply effected was a composite supply or not. I also find that its findings on the said issue are at any rate legally untenable. The concept of enhancement of utility of the instrument through the supply of reagents/calibrators/disposables, while relevant for the purposes of valuation of the supply of instruments, cannot be imported into the concept of composite supply under the GST Act. A distinction has to be drawn between the nature of a supply and the valuation thereof. While clubbing of two independent supplies may be resorted to for the purposes of valuation of each of those supplies, there is no scope of clubbing of two independent supplies so as to notionally alter the very nature of each of those supplies as they existed in fact, at the relevant point in time. For a supply to be seen as a composite supply, it must answer to the definition of the term “composite supply” at the time of its supply. As per Section 2(30) of the CGST Act, “composite supply” means: “a supply made by a taxable person to a recipient consisting of two or more taxable supplies of goods or services or both, or any combination thereof, which are naturally bundled and supplied in conjunction with each other in the ordinary course of business, one of which is a principal supply.” 9. Many aspects of the transactions envisaged under the agreement entered into between the petitioner and its customer hospitals/laboratories militate against viewing them as a composite supply as defined above. Firstly, the supplies are made by two different taxable persons; the supply of instrument being by the petitioner and the supply of the reagents, calibrators and disposables being by his distributor, who purchases it from him on principal to principal basis. Although it could be argued that there is a relationship between the said persons that influences the valuation of the supply, the same does not take away from the fact that the supplies are, in reality, made by two different taxable persons. A reference can usefully be made to the decision in Nell Gwynn House Maintenance Fund Trustees v. Customs and Excise Commissioners [(1999) Simon's Tax Cases 79 (HL)] as also to the decision in Telewest Communications PLC v. Customs and Excise Commissioners [(2005) Simon's Tax Cases 481 (CA)]. In the last mentioned case, while reiterating that the concept of a composite supply would not be attracted in cases where there was more than one supplier, the Court of Appeal observed as follows: “ xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx (3) There were limits to the extent to which transactions could be recharacterised in VAT law and taxable persons denied the exemptions on which they sought to rely. Moreover, there was no authority for the proposition that the concept of principal and ancillary contracts could apply where there was more than one supplier, nor that where one supply could be said to be ancillary to another, even though they were made by separate suppliers, both suppliers had to share the same tax treatment. Indeed, supplies by two separate suppliers could not be treated as principal and ancillary supplies. Furthermore, there was an objection in principle to and strong policy reasons against taxing transactions according to their economic reality. The economic reality of a transaction was antithetical to legal certainty. The mere fact that the court sought to find the commercial reality of the situation did not mean that it would seek to apply VAT to the economic reality of the transaction. The economic reality of the transaction might have nothing to do with either the essential features of what the parties had agreed or the legal structure of their transaction. Moreover, economic reality had to be distinguished from economic neutrality which was a principle of VAT law. That principle precluded, inter alia, taxable persons who carried on the same activities from being treated differently for VAT purposes. That was one of a variety of doctrines which had been established in VAT law to prevent the distortion of competition. However, the authorities did not support the proposition that the doctrine of neutrality required two separate supplies to be treated as a single supply because the suppliers were related parties and their supplies were linked. xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx” 10. Secondly, the two supplies do not answer to the description of being “naturally bundled and supplied in conjunction with each other in the ordinary course of business”. While they were not bundled together as a matter of fact, in the instant case, there is also no material to suggest that they are so bundled and supplied in conjunction with each other in “the ordinary course of business”. In fact, the business model followed by the petitioner appears to have held the field for a considerable period of time and would show that in the ordinary course of business, the supplies are not bundled. In my view, a finding as regards composite supply must take into account supplies as effected at a given point in time on “as is where is” basis. In particular instances where the same taxable person effects a continuous supply of services coupled with periodic supplies of goods/services to be used in conjunction therewith, one could possibly view the periodic supply of goods/services as composite supplies along with the service that is continuously supplied over a period of time. These, however, are matters that will have to be decided based on the facts in a given case and not in the abstract as was done by the AAR. I therefore allow the writ petition, by quashing Exts.P1 and P2 orders, and remit the matter back to the AAR for a fresh decision on the query raised before it by the petitioner company. The AAR shall pass fresh orders in the matter, based on the observations in this judgment, and after hearing the petitioner, within a period of six weeks from the date of receipt of a copy of this judgment. The writ petition is disposed as above.

Download the copy:

ConsultEase Administrator

ConsultEase Administrator

Consultant

Faridabad, India

As a Consultease Administrator, I'm responsible for the smooth administration of our portal. Reach out to me in case you need help.